Article by John Kehoe, courtesy of The Australian Financial Review.

There is something seriously wrong with the federal budget.

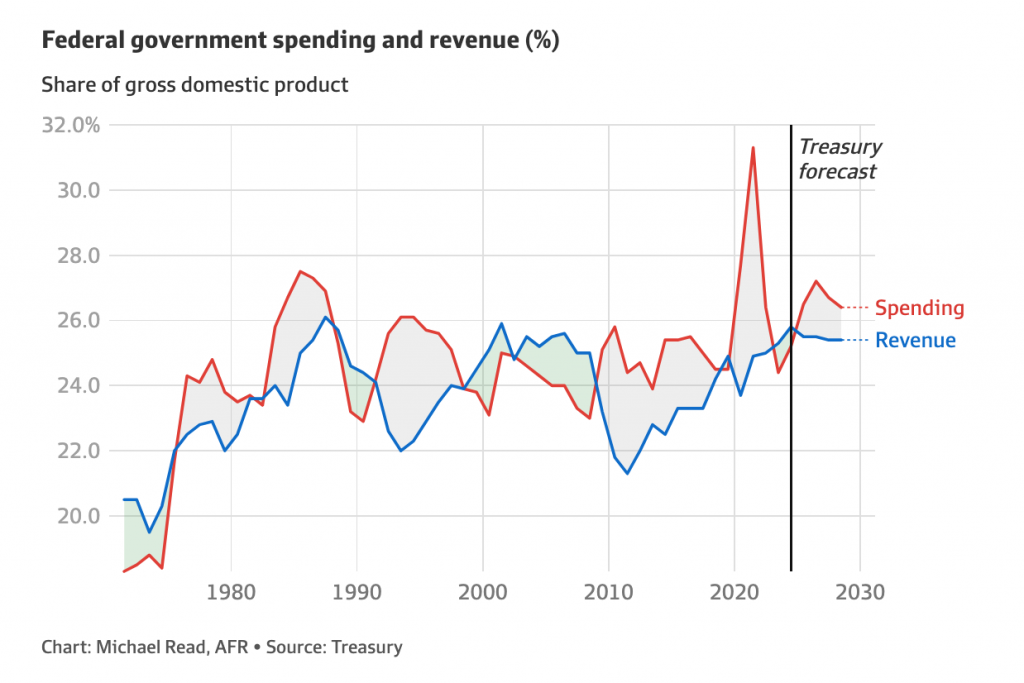

Tax and other government revenue are hovering near a sustained record high of 25.5 per cent of the economy thanks to once-in-a-generation windfalls.

The unemployment rate is a very low 3.9 per cent and personal income tax is on track for a record $335 billion this year, despite the stage 3 income tax cuts shaving off about $23 billion.

Company tax of $133 billion is just a bit below its all-time high last year, amid elevated commodity export prices.

Total budget revenue is cumulatively more than $380 billion higher over five years compared with Treasury’s forecasts on the eve of the May 2022 election, economist Chris Richardson calculates.

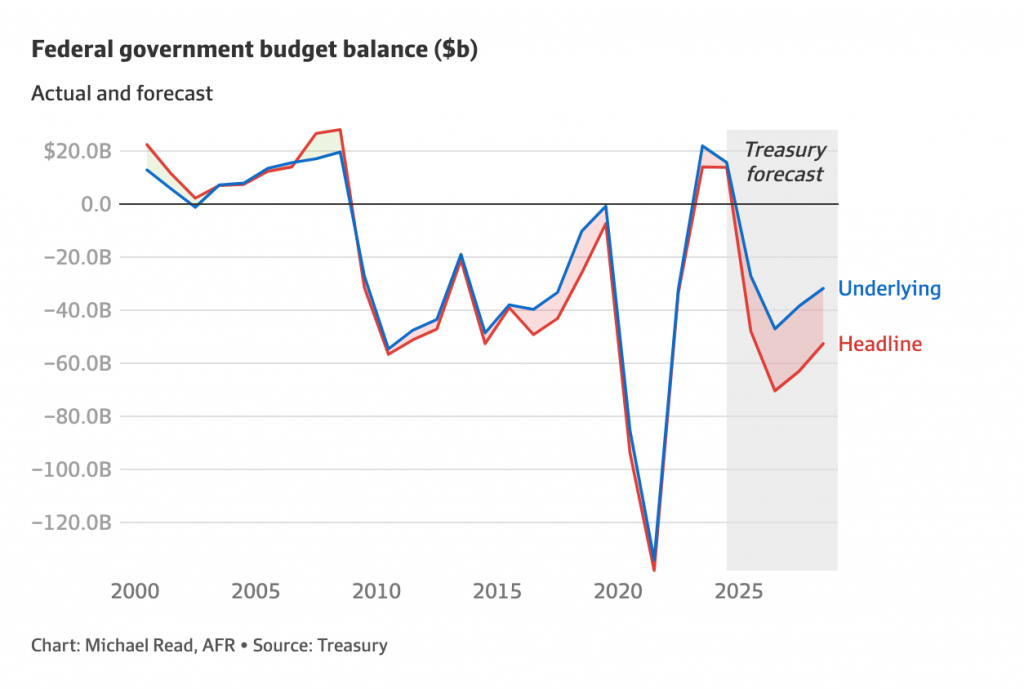

Yet, at a time when revenue is booming and the economy is operating around full capacity, the deficit in underlying terms is forecast to be $26.9 billion (1 per cent of gross domestic product), a $1.3 billion improvement since the May budget.

Cumulative underlying deficits over four years are projected to blow out to $144 billion, $21.7 billion worse than expected seven months ago.

But that is not the full story.

The underlying budget balance that treasurers prefer to focus on hides a heap of so-called “off-budget” spending, such as taxpayer money for the Clean Energy Finance Corporation, the $12 billion Snowy Hydro 2.0 project, wiping 20 per cent off student debts and the $15 billion National Reconstruction Fund.

Adding in the government’s extra below-the-line spending, the headline cash deficit is $47.8 billion this year and a whopping $233 billion over four years to 2027-28.

The Coalition also plans to add hundreds of billions of dollars to off-budget spending in the long term for nuclear energy.

Why are deficits blowing out when revenue is soaring? The answer is runaway spending.

Federal spending as a share of the economy will hit 27.2 per cent in 2025-26 – the highest outside the pandemic since 1986, just before the Hawke-Keating Labor government began a fair dinkum fiscal repair mission.

But Treasurer Jim Chalmers and Finance Minister Katy Gallagher show no sign of emulating their Labor predecessors Paul Keating and Peter Walsh.

The $50 billion National Disability Insurance Scheme is the chief spending culprit, despite attempts to restrain it. Annual growth in the NDIS is projected to fall from 20 per cent to a still very high 8 per cent to hit $93 billion a year by 2033-34, the government actuary estimates.

Childcare subsidy spending has blown out by a further $3.1 billion over four years, even before Labor is expected to announce a big new universal childcare package in the new year.

Total real spending growth, even discounting for the high inflation rate, is running at an unusually high 5.7 per cent this fiscal year. In nominal terms, it is 8.7 per cent.

Government spending is increasing at a rapid clip, while the Reserve Bank of Australia has its foot firmly on the interest rate brake trying to stamp out inflation. By the government’s own numbers, fiscal policy is working in the opposite direction of monetary policy.

Real government spending growth was originally budgeted in October 2022 to be a relatively low 1.8 per cent in 2024-25. The almost 4 percentage point blowout shows why Chalmers’ claim that average real spending growth will be 1.5 per cent over the six years to 2027 28 is a charade because it fails to factor in inevitable new future spending.

The government blames $8.8 billion of “unavoidable spending” this year and $47.6 billion in total it inherited from the former Coalition government since coming to office, such as for unfunded and expiring programs.

Examples include payment variations to ensure veterans receive their entitlements, indexing pensions, increasing support to families, disaster recovery funding and increased demand for health services.

Undoubtedly, there is some compulsory extra spending that cannot be avoided.

But the job of any government is to consider the trade-offs of different spending programs, prioritise and make room by cutting wasteful spending and saying no to new ideas.

Richardson calculates the government’s net spending and taxing decisions since the election have worsened the budget by $78 billion over five years.

After some semblance of restraint by Labor to deliver two surpluses, fiscal discipline is slipping as the election approaches.

A federal and state government spending splurge forced Treasury to upgrade public final demand growth to 3.75 per cent, from 1.5 per cent expected in the May budget.

Regrettably, Treasury and Finance failed to impose meaningful budget rules on the government, as The Australian Financial Review has repeatedly warned since Labor’s first budget in October 2022.

Taxpayers will pay the price for this inertia.

Labor under Bill Shorten at the 2019 election was honest enough to explicitly outline tax rises to pay for higher social spending,

The Albanese government prefers a tax-and-spend agenda by stealth that will inevitably lead to higher income taxes over the medium term as bracket creep squeezes working-age people.

The other worry is there is more likely election spending from both sides still to come.

When the mining export boom eventually ends, Australia’s broken budget will be fully exposed and look very ugly.