Afrustrated crowd of mining industry diehards erupted into applause when Richard Laufmann, the managing director of copper explorer Rex Minerals, warned against tinkering with one of the sector’s most sacred documents.

“We shouldn’t be complicating ourselves out of existence,” Laufmann told the investors and geoscientists gathered in the basement of Melbourne’s Le Meridien Hotel last month.

Between bottles of Asahi and trays of arancini, about 100 had gathered to debate proposed changes to the code that governs how mineral deposits can be reported to investors in Australia, New Zealand and Papua New Guinea.

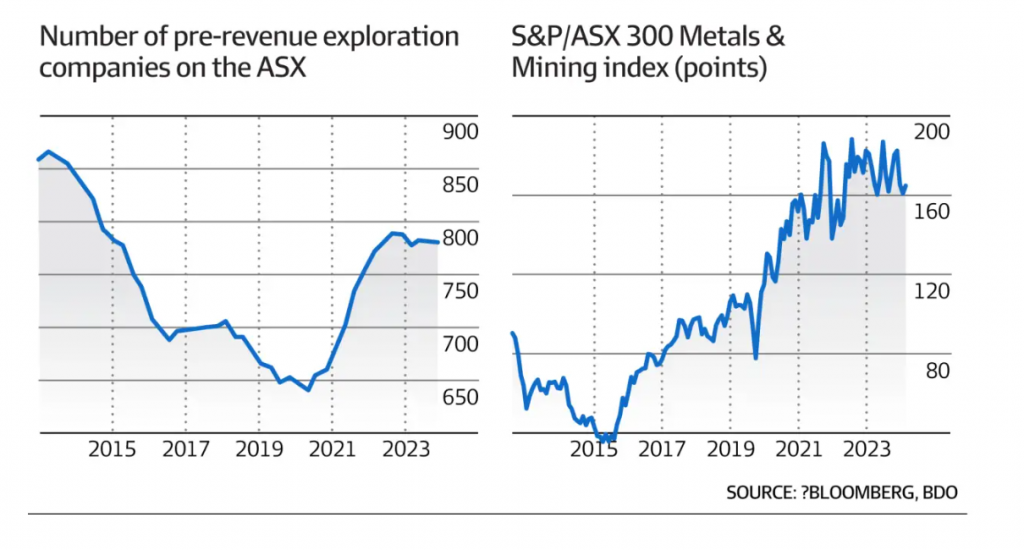

That code, known as JORC, is the little-known foundation stone upon which $544 billion of market value is built into the S&P/ASX 300 Mining and Metals Index. The code is particularly important for the 775 explorers on the ASX who have yet to report any revenue; their combined market capitalisation of $58.8 billion is almost entirely determined by JORC-compliant declarations about the size and quality of their undeveloped mineral discoveries.

For the ASX these tiny explorers are collectively too big to fail; they represent almost 40 per cent of all listed companies on the bourse.

“Complication is hurting us every day,” Laufmann told the gathered crowd in Melbourne. “We are making it more and more difficult for our investors, to tell them what we have.”

That meeting was one of many underway across the country giving the industry a chance to provide feedback on the first major changes to the JORC (Joint Ore Reserves Committee) code in 12 years. Those changes represent a fundamental shift – one that proponents say is needed to better protect investors, bringing environment, social and governance considerations in for the first time in its near-six decade history.

The JORC code was born out of bad behaviour; the nickel boom of the 1970s was plagued by highly dubious claims, and the industry responded by trying to create a single set of rules against which all mineral deposits should be measured and promoted. Since then, it has been updated five times.

Now, the keepers of the code – industry associations like the Australian Institute of Geoscientists, the Minerals Council and the Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy – want to force companies to declare how ESG considerations will affect the viability of their discoveries.

ESG factors are increasingly capable of killing projects, even if they have attractive geology. Native titleholders’ desire to protect cultural heritage has condemned the Jabiluka uranium deposit, while government policies to cut emissions and protect biodiversity may yet threaten the viability of the Worsley alumina refinery. Last week, Regis Resources cancelled a $1 billion gold project in NSW last week because of hotly contested cultural heritage concerns.

A draft update of the code says ESG factors should be treated with equal importance to the things the code has traditionally prioritised, such as whether the metallurgy of the discovery would allow for commercial extraction.

It also calls for ESG threats to be disclosed as early as possible, meaning micro-cap explorers may be forced to consider softer concepts.

Those changes are an anathema for many in the geoscience community, who consider their work to be limited to making quantitative assessments of the grade and depth of mineral discoveries. The changes could force them to also make qualitative judgments about the levels of support within local native title groups or the environmental significance of nearby wetlands.

“The other risks should come later,” said Laufmann to the Melbourne event, arguing for the code to remain a scientific one, rather than span everything from hydrology to anthropology.

Veteran geologist Steve Hunt was standing in front of the Melbourne audience when Laufmann spoke up.

As chairman of the group of volunteers that came up with the draft changes, Hunt will spend most of the next month touring and explaining why reform is needed.

“Somewhere between a rock star and a target for people throwing rocks,” says Hunt of his role as the face of the proposed changes.

Hunt wasn’t surprised by Laufmann’s comments. But he is convinced that the mining industry must move with the times.

“People hear ESG and get the red mist in their eyes and say ‘You are just making our life harder.’ Well actually, that hardness is in the process that is already there,” he says. “The rapidly changing approvals environment is causing people a lot of stress. But they are the gates we have to pass through to get mining opportunities developed in today’s world. We can’t wish it away.

“When you do an update [of the JORC code], you are doing it for the next 10 years, not the previous 10 years,” says Hunt.

More calibration than revolution

The increasing focus on ESG factors has some geoscientists fearing they no longer possess all the skills required to complete the sort of legally binding assessments that are routinely disclosed to the sharemarket. If the draft changes are adopted, many industry players believe a JORC assessment will require a larger number of professionals with a wider range of skills, which shapes as a recipe for higher compliance costs.

But Hunt says that most of the work is already being done.

“You have to do a lot of heritage and environmental clearances to do your very first set of drill holes on any exploration property in Australia right now,” he says. “[The JORC draft] doesn’t say, ‘Go and do a $10 million study to feasibility level before you drill your first drill hole.’ We are not saying that. What we are saying is, ‘If you have got it [knowledge of an ESG factor], it should not be invisible. If you know about it, you can’t conceal it.’”

Most of the town halls have been robust but respectful. But Monday will be a litmus test, when Hunt’s tour begins a five-day swing through the mining epicentre of Perth.

It has been a hard year on the mining sector’s western front. Major players like BHP, Alcoa and Fortescue have cut thousands of jobs, and a commodity price downturn is shredding valuations for everything but gold.

The West Australian mining industry is not afraid to throw its weight around. Last year it succeeded in getting the state’s new Indigenous heritage laws repealed within a month. Now, the industry has Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek’s “nature positive” reforms firmly in its sights.

Hunt won’t be surprised if those attending meetings in Perth push back against the proposed changes to the JORC code, too.

“There is a lot of existential pain in the junior exploration industry at the moment, and anything that feels like an extra burden is absolutely not welcome, so we know we will get feedback in that form,” says Hunt.

“But we’ve also got [investors at] the other end saying, ‘What you are proposing is still too soft, and you should make it harder’. This is more calibration than revolution, but it underpins the ability for investors to look at all the options and figure out where they want to put their money.”

Luke McFadyen runs pre-revenue exploration company Minerals260 and will be in the crowd in Perth on Monday. He said any changes to the JORC code should focus on how to accelerate project developments – not bog them down.

“It’s important for the long-term survival of the exploration and mining industry that Australian companies are not disadvantaged with unduly onerous rules and regulations that our international competitors do not have to abide by,” he says.