Article by Kevin Crowley and Will Mathis, courtesy of Bloomberg.

The chief executive of BP Plc oozed confidence as he strode out onto a Houston stage in 2023 to tell an audience of fellow oil executives that he no longer ran an oil company.

“I lived in America long enough to know that when you’re getting an electric F-150, the world is going electric,” Bernard Looney, then in his fourth year running the company, told the attendees at CERAWeek by S&P Global, one of the world’s premiere oil conferences. “Our strategy is to transform BP from an international oil company to an integrated energy company.”

Two years later, Looney is out of his job and BP has not become the low-carbon, fuels-of-the-future giant it wanted to be. Far from it.

The company is now in turmoil after a plunge in its shares made it the target of one of Wall Street’s most aggressive activists. Murray Auchincloss, BP’s current CEO, last week pledged to “fundamentally reset” the company’s strategy, increasing spending on oil and gas nearly 20%, to $10 billion a year. He also slashed investments in clean energy, biofuels and batteries. (Looney was even proved wrong about electric pickup trucks; Ford Motor Co. has lost billions on its marquee EV, far overshooting consumer demand.)

After years of exploring the future beyond petroleum, as promised in BP’s long-discarded advertising slogan, the world’s supermajor oil companies are now reverting to the same fossil fuel-focused strategy that fed their profits — and rising global temperatures — over the past century. The next era will come with a new emphasis. Executives will now likely argue natural gas is needed to power the artificial intelligence revolution. But what gets left for dead is the idea that Big Oil will transition to Big Energy, underscored by US President Donald Trump’s return to the White House.

“They’ve chosen to take a backseat rather than a leadership position,” said Shu Ling Liauw, CEO of Accela Research Ltd., a climate-focused investment adviser. “The integrated energy company concept is off the table.”

Five years ago, these same oil giants seemed to be at a turning point. A decade of poor returns from overspending on megaprojects hurt the industry’s reputation on Wall Street. Their fossil fuel-focused business model appeared at odds with the Paris Agreement’s goals to hold global warming below a 2C increase from preindustrial temperatures.

Pressed by shareholders and the movement for investing driven by environmental, social and governance factors, all the supermajors eventually pledged to do more to address climate change. Investors essentially asked to “deliver all the renewables but with the same returns as oil and gas,” said Nick Wayth, who spent over 20 years at BP and helped guide the company into solar and offshore wind. “I don’t know if it was doomed to fail, but it was always going to be very challenging.”

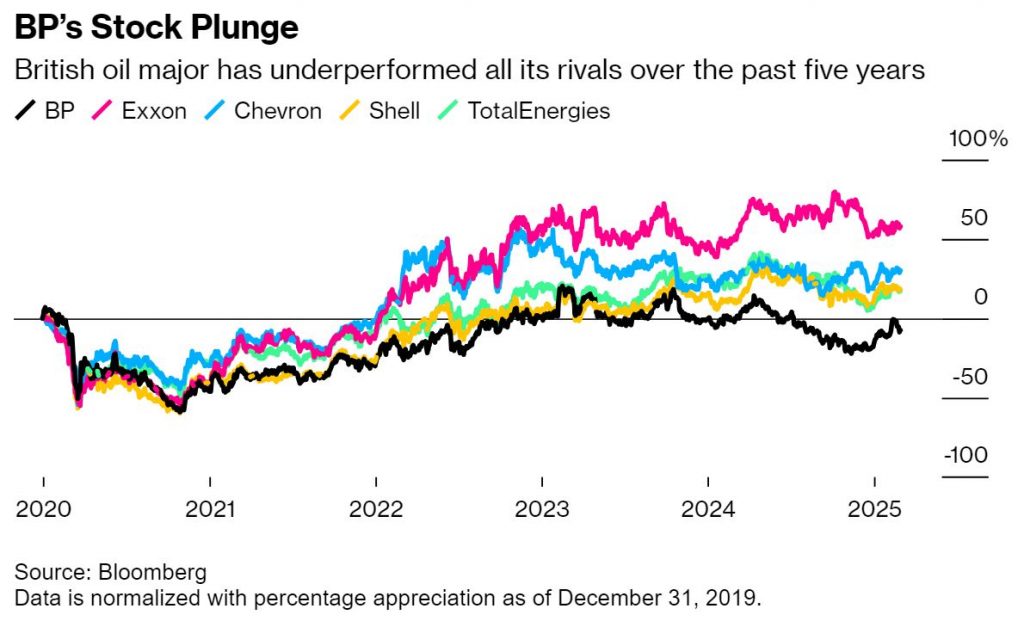

A split emerged between the Americans and the Europeans. Exxon Mobil Corp. and Chevron Corp. focused on cleaning up their own operations and invested in technologies like carbon capture and hydrogen that are widely seen as part of the net zero future. It helped that these technologies fit neatly into energy systems already powered by fossil fuels and are supported by government incentives. But both American oil giants refused to kill the golden goose, even after Exxon lost a climate-charged activist battle in 2021. Instead, Exxon and Chevron have increased oil and gas production 15% and 9%, respectively, since the end of 2019.

By contrast, BP and Shell Plc invested heavily in power to be at the forefront of the electrification trend that would drive the world toward net zero. But crucially, their investments in everything from wind and solar generation to EV charging stations came at the the expense of oil and gas, which made up the bulk of their cashflow. In 2020, BP expected its oil and gas production would drop 40% within the decade. Shell anticipated a gradual decline of 1% to 2% annually.

These two diverging paths had significant implications for net zero because the world’s biggest investor-owned integrated oil companies have an outsized influence on the future direction of fossil fuel emissions. Despite only producing about 10% of the world’s crude, they tend to lead the largest oil and gas projects, and their technology helps drive exploration for new resources. Leaving their reserves in the ground — along with all those potential greenhouse gas emissions — would help slow the devastating increase in global temperatures.

The results from Wall Street are now in. Exxon shares have climbed 58% since the end of 2019 — and BP is down 7.3%. Chevron has significantly outperformed Shell. There were plenty of unforeseen circumstances, including Russia’s invasion of Ukraine causing record fossil fuel profits in 2022 and rising interest rates eroding returns on renewables. But the difference is too big for investors to ignore.

“The Europeans learned the hard way that investors want to see their capital deployed in a disciplined manner — they want to see a rate of return on that capital,” said Ben Cook, a Dallas-based portfolio manager at Hennessy Funds, which oversees about $5 billion. “If you have to cut your dividend and share repurchases because of investments in renewables then you’re going to get a haircut in your valuation.”

TotalEnergies SE appears to be threading the needle between fossil fuels and electrification. The Paris-based company funds its focused investments in solar, wind and batteries by increasing oil and gas production. “I need the cash in charge if I want to finance the diversification,” CEO Patrick Pouyanne said at International Energy Week in London in February. “I need to maintain this dance. I need to continue to develop oil and gas.”

BP is not the only supermajor to row back on net zero to chase a higher stock price. Last month Shell wrote off almost $1 billion as it withdrew from a US offshore wind farm that became the target of Trump’s executive orders. Norway’s Equinor ASA recently reduced its 2030 target for renewable generation.

Orsted A/S was once the poster child for net zero. The company is one of the few to truly transition away from oil and gas while reinventing itself in offshore wind. But even that transformation looks gloomier in retrospect. The company axed its dividend last year due to spiraling costs, and its shares are down 56% since the end of 2019.

The investor drive for better performance on emissions has completely changed now, according to Andy Brown, a former executive at Shell who now serves as deputy board chair at Orsted. “That pressure is off, and now it’s about how you maximize returns,” he said in an interview in London. “The fundamental business model for renewables is challenged today.”

Wall Street’s message of disciplined capital spending and high shareholder returns applies as much to fossil fuels as it does to renewable energy, as the US oil majors are finding out.

Despite their relative success versus their European peers, Exxon and Chevron trade at a 30% discount to the S&P 500 Index in large part due to investor concern over the longevity of oil demand. The US is now the world’s biggest oil producer, pumping 50% more barrels each day than Saudi Arabia, yet energy makes up just 3.3% of the wider index.

To improve their position with investors, the two US giants are not trying to produce as much oil and gas as they can. Rather, they’re hyper-focused on pumping as cheaply as possible. It’s the “last man standing” strategy: If producers can get costs low enough, others will withdraw from the market first, allowing them to make money even if the energy transition eventually collapses demand for oil.

Exxon aims to get its breakeven oil price down to $30 a barrel by 2030 by growing low-cost production in Guyana and the Permian Basin and selling its higher-cost operations. Brent crude traded for $74 a barrel at the close on Feb. 27.

After recently starting-up its enormous Tengiz development in Kazakhstan, Chevron has a dearth of major new projects beyond 2030. It reduced its capital spending budget this year for the first time since 2021, will lay off 20% of its workforce by next year even after returning $27 billion to shareholders in 2024.

Big Oil “has got incredibly good at moving down the cost curve,” said Noah Barrett, Denver-based lead energy research analyst at Janus Henderson, which manages about $380 billion. “That means they’re not scared of peak oil demand, it’s unlikely to be as dire for the industry as some have predicted.”

Robert Johnston, research director at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy, argues that it would be dangerous for oil executives to turn away from low carbon after just a few years of bad returns accelerated by a pro-fossil fuel Trump administration. “For 2025, it looks like the Americans are right and the Europeans are wrong. But the C-suite needs to be looking at the next 20 years,” he said. “The longer view is that there’s a huge market opportunity for the right low carbon investments.”

It doesn’t look like Big Oil is ready to make that leap anytime soon.

“That’s the sad fact today — nobody will pay us for emissions reductions,” Exxon CEO Darren Woods said in an interview in November, on the sidelines of the annual United Nations climate summit. Sure, Exxon could produce green jet fuel. “But no airline will sign a contract with me to provide it because it’s more expensive.”

“That’s the challenge of the transition is it’s going to be more expensive,” Woods concluded. “And today the market won’t bear that additional cost.”