Article by Elouise Fowler and Mark Wembridge, courtesy of Financial Review

24.08.2025

The $1.2 billion lithium hydroxide refinery on the shores of Perth’s southern beaches was once heralded as vital to Australia’s dream of becoming a battery minerals processing powerhouse.

Today, the Tianqi Lithium plant sits in an uneasy state – its expansion plans in tatters, its future bleak. Conveyor belts that once ferried lithium-rich rock to a 1000-degree kiln and onto a vat of chemicals lay idle for long periods at the start of the year.

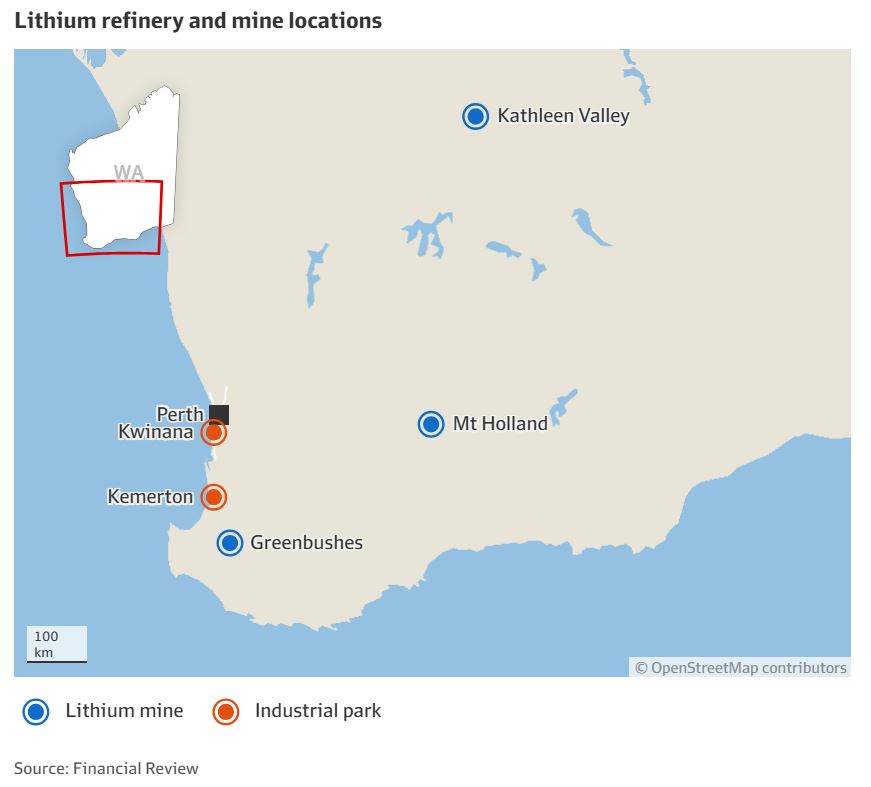

Plans to double the size of the plant – a short drive from Perth in the industrial suburb of Kwinana – were shelved in January. High costs, low lithium prices, technical problems and unfavourable economics are conspiring to kill off the facility entirely, and with it another slice of Australia’s dream.

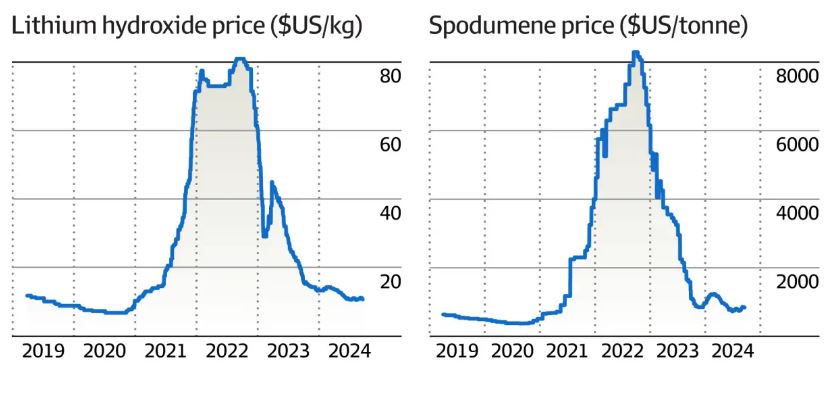

In the past two and half years, the price of lithium – a mineral critical to the renewable energy transition and used in the manufacture of rechargeable batteries for electric vehicles and homes – has plunged almost 90 per cent, due to oversupply and weaker-than-expected electric vehicle demand. Miners from Australia to China to South America rushed to bring production online in anticipation of unprecedented demand. Instead, the lithium boom turned into a spectacular bust.

While some observers believe prices have bottomed, miners, refiners and car manufacturers are still working through a supply glut, which is clouding the future of projects such as Tianqi Lithium.

“It wasn’t economically viable,” explains Tianqi – the Hong Kong-listed group that operates the Kwinana joint venture with Australia’s IGO – of its expansion plans. Barrenjoey metal and mining analyst Daniel Morgan is more blunt in his assessment. “We value Kwinana at zero, as do most of the investors,” he says.

Despite having spent more than $1 billion to establish the facility, the economics behind an expansion to double its output do not add up, laments Ivan Vella, IGO’s chief executive. “Australia offers no distinctive advantage in the business of lithium chemical processing or, for that matter, any of the major mineral processing downstream industries,” says Vella. “Any investment in downstream processing needs to be competitive on a global scale.”

China dominates the market for critical minerals, including 90 per cent of lithium processing, and the price rout has reinforced its dominance over the sector as Western projects falter.

Wary of China’s global dominance in the supply chain of critical minerals, governments such as Canada, Australia and the United States have pushed to secure local sources and wrest control away from Beijing. As such, suppliers were betting that a “non-China premium” for their processed lithium would eventuate.

Yet, the stark reality is that despite political rhetoric about supply chain security, cost efficiencies remain king in the lithium market and the lowest price producers are winning. Beijing is renowned for keeping a lid on prices to thin out global competitors. Lithium is no exception.

Australia is not only playing catch up with China, it also offers distinct disadvantages including higher costs to build facilities and more expensive energy. “Capital intensity [the cost to build a plant] here is 10 times what it is in China, and operating costs are higher,” says Kate McCutcheon, an analyst at Citi.

Operating expenditure is also significantly higher – it is estimated that China can process a tonne of lithium salts for $3000 to $4000, while Citi estimates Tianqi’s costs in Western Australia are double that figure.

China also harbours an abundance of lithium processing expertise to call upon, while Australia’s talent pool in the nascent industry is relatively shallow. “Australia is an expensive market to operate in, but these refiners have also struggled with technical problems specific to their construction and a shortage of technical know-how,” says Martin Jackson, the lead battery minerals analyst at Cru, a London-based consultancy.

Processing prospects fade

The woes of the plant – Tianqi’s first outside China – reflects the fading prospects for downstream lithium processing in Australia.

Just a few months before Tianqi scrapped its expansion plans and slowed production, New York-listed Albemarle binned its $4 billion ambition to quadruple its lithium hydroxide facility in Kemerton, another industrial park on WA’s south-west coast.

Despite these substantial setbacks, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese appears determined to try and keep the processing ambition alive. His instrument of choice is a 10 per cent tax break under Labor’s “Future Made in Australia” policy for critical minerals processing and refining.

“We can build a future for Australia with thriving industries,” Albanese declared after the Senate passed the $7 billion of tax incentives in February. “Just like the governments of John Curtin and Ben Chifley after World War II.”

The policy, slated to run for up to a decade from 2027, seeks to encourage companies to enhance the value of Australia’s vast mineral resources before exporting them.

By fostering domestic processing and refining, the initiative hopes to bolster the country’s industrial capabilities and offer an alternative supply for businesses looking to reduce dependence on China.

However, it will take more than a tax break to restore the fortunes of the industry in Australia. Already reeling from technical setbacks and depressed prices for the key battery metal, the US last August delivered a hammer blow to the struggling Australian sector.

Bureaucrats in charge of tax breaks for lithium sourced from US-allied countries refused to back projects connected to the Australian lithium mine Greenbushes, citing its ties to China. The mine – the world’s largest hard-rock lithium mine located in southern Western Australia – is 49 per cent owned by Albemarle, while Tianqi owns the controlling stake along with ASX-listed IGO. The mine produces nearly half the global supply of lithium-rich spodumene ore.

The US ruling was the final straw for Albemarle’s plans in Australia and killed off the project’s expansion.

“Our strategy had been to pivot to the West,” Albemarle’s chief executive Kent Masters told investors last year. “We’ve backed off that, given that prices have been so low and economics of building that supply chain out in the West. We still hope to do that, but we have to wait and see what a Trump administration wants to do.”

Donald Trump’s plans for Australian critical minerals are uncertain. The erratic president proposed a US takeover of Greenland and a critical minerals deal with Ukraine. However, his administration rejected the Albanese government’s offer of guaranteed access to Australia’s critical minerals in return for sparing the country’s steel and aluminium exports from tariffs. Regardless, the federal government hopes that access to these vital resources can be used as a bargaining chip in future negotiations.

The downstream boom

Politicians wanting Australian miners to expand their downstream processing ambitions is nothing new.

Most of the seminal state agreements created in the 1960s and 1970s for the nation’s biggest resources projects – the iron ore mines of WA’s Pilbara, the oil and gas in the state’s North West Shelf, the bauxite in its Darling Range and the mineral sands of the south-west – only gave miners permission to dig if they attached domestic processing and refining.

In most cases, the miners never delivered on those promises, and when they did try, they typically failed, as demonstrated by BHP’s hot briquetted iron disaster at Port Hedland and Rio’s failed Hismelt factory at Kwinana.

Australians seemed to accept the idea of dig-and-ship in the early part of this century because the riches that rolled in from iron ore and coal from the China boom were so vast. But when the first lithium boom emerged in 2015, the temptation of a domestic refining industry returned to the fore.

Lithium miners – without pressure from politicians – outlined grand plans to turn WA into a key battery metal refining hub as lithium prices rocketed on rosy prospects for electric vehicle sales. That vision was not unfounded. The rapid shift toward electrification and renewable energy in China and across the globe, at a pace the world has never seen before, sent lithium prices soaring as supply was scarce. But while the ore was being dug out of the ground in massive quantities fetching staggeringly high prices, most of its value was being captured overseas – mainly in China, which processes three-quarters of the world’s battery-grade lithium.

“In theory, it makes a lot of sense for us to have downstream processing here because it’s next door to the best hard rock lithium deposits globally,” says Citi’s McCutcheon. “You should be saving $200 a tonne on freight. There’s an environmental, social, and governance benefit too because you’re not shipping 95 per cent waste across to Asia to be refined.”

Moreover, the simmering trade war between Washington and Beijing meant US and Chinese companies alike saw an opportunity to add value in Australia by developing a supply chain outside of Beijing’s control, shielding operations from the fallout from a potential trade war. “For lithium and critical minerals, there is a dependency concern over China and I think there is a market failure,” says Adam Triggs, a partner at economics consultancy Mandala.

Just after prices for lithium-rich spodumene hit $US6000 per tonne during the first boom in 2017, and lithium hydroxide passed $US20,000 per kilogram, Albemarle revealed plans to build a $4 billion plant in WA that would have four units, known as “trains”, to produce lithium hydroxide for battery makers.

The Australian miners would dig lithium-rich spodumene, while the downstream facilities would process it into lithium hydroxide. The sprawling complex at Kemerton, near Perth, would capitalise on Albemarle’s 49 per cent stake in the Greenbushes mine.

The second lithium boom in 2022 – when unprocessed spodumene prices soared to $US8000 per tonne – strengthened the case for expanding Australian downstream processing. By 2023, Albemarle was preparing to acquire ASX-listed Liontown Resources in a landmark $6.6 billion deal. Liontown’s Kathleen Valley lithium mine, alongside supply from Greenbushes, was set to support the US battery giant’s ambitious plans for a vast downstream processing network in Australia.

Wesfarmers, the ASX-listed conglomerate, followed suit when it unveiled plans to push forward with a $2 billion-plus lithium hydroxide refinery, also in Kwinana, near Tianqi.

Known as Covalent Lithium 50/50 joint venture, alongside Chilean partner SQM, it will produce lithium hydroxide from its Mount Holland mine. The facility is due to come online at the end of the year.

Washington’s cold shoulder

Australia’s lithium processing push was ill-timed, coinciding with a market glut and plummeting prices.

Amid the market carnage, Albemarle’s takeover of Liontown Resources was abandoned, while lithium hydroxide projects that have survived now face delays, budget cuts or indefinite suspensions as companies scramble to preserve cash.

But falling prices are only part of the story. Australia’s critical minerals industry also found itself caught in the middle of a geopolitical tug-of-war between the US and China.

The Albanese government had hoped that the Inflation Reduction Act – former US president Joe Biden’s sweeping green energy subsidy package – would turbocharge investment in Australian processing. It was designed to re-industrialise the US Rust Belt and pivot away from China by incentivising manufacturers to buy commodities from allied countries.

But the opposite occurred. Under pressure from Washington to curb Chinese influence in supply chains, US government agencies disqualified Greenbushes under its “foreign entity of concern” rules because Tianqi owned more than 25 per cent of the mine. Albemarle’s inability to qualify for billions of dollars of subsidies under the IRA proved fatal to its expansion.

“The US decision was a huge moment,” says Lian Sinclair, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Sydney’s School of Geosciences. “The foreign energy of concern rules are sensibly designed. But in this case, … I’m surprised an exemption wasn’t given.”

A future made in Australia?

While the grand vision of an Australian refining powerhouse is fading, Albanese continues to express confidence in the dream. The government is rolling out advertisements that trumpet the Future Made in Australia plan that is shaping up to be the most interventionist policy in decades.

Yet, the Future Made in Australia production credits cannot alone save downstream lithium processing.

The agenda depends largely on a green or geostrategic premium – that is, customers willing to pay above the normal market rate for products that are low-carbon or avoid China’s supply chains. That sentiment underpinned IGO’s decision to enter the joint venture with Tianqi. “They envisaged that customers would pay an ESG [environmental, social and governance] premium for the hydroxide from its Kwinana plant,” says Citi’s McCutcheon. “That’s great in theory, but it’s not how markets work.”

China, for the foreseeable future, will continue to be the dominant player in lithium processing, and governments wanting to challenge that will need to provide large support packages, says Cru’s Jackson.

Both Albemarle and Tianqi’s existing facilities have been plagued by technical setbacks, and neither have come close to producing their maximum output. Tianqi processed 3500 tonnes in the past financial year out of an annual capacity of 24,000 tonnes. Albemarle’s is also far from its 25,000-tonne target.

Meanwhile, talk of new lithium hydroxide plants – once a staple of miners’ investor presentations – has all but disappeared.

Still, Wesfarmers is optimistic and has backed the introduction of the production tax credit. “The construction of these large-scale projects requires many years of investment before returns can be generated, so targeted government assistance enables the industry to get established, and in the long term, brings substantial benefits to the economy and community,” the conglomerate says.

Other Australian miners are looking offshore. Rio Tinto owns a lithium hydroxide plant in Japan’s Fukushima acquired from Arcadium, while Pilbara Minerals has a joint venture with South Korea’s POSCO.

Unless lithium prices recover dramatically, the boom-time dream of a self-sufficient, geopolitically insulated lithium refining industry in Australia may be just that – a dream.

Still, some believe that government intervention can counter this.

“We have the processing knowledge. What we don’t have is the processing incentive,” Kim Beazley, a former federal opposition leader and ambassador to the US, says of Australia’s goal of creating a downstream processing industry for critical minerals, specifically rare earths.

“Australia can [create a processing industry] if people are prepared to invest money without expecting any major returns, if any, for a period of time,” he says. “We’ve got to be what we once were, which is strategic. We’ve got to be what the Chinese are now, which is strategic. The market won’t resolve any of this.”